Home » Publications »

Discovering Literature: 20th Century: An introduction to Our Country’s Good

Our Country’s Good by Timberlake Wertenbaker tells the story of members of the British Navy and convicts in a penal colony putting on a play in 18th-century New South Wales. Sara Freeman examines how Wertenbaker uses the structure of a play within a play to explore themes of colonialism, authority, transgression and the power of narrative.

Timberlake Wertenbaker’s 1988 play Our Country’s Good

tells a story based on historical events and features a play within the play. Part of the play’s power stems from how it connects past and present through documentary information and metatheatrical performance. The play creates tension and insight by recording the pain and injustice suffered by its cast of convicts, while suggesting the potential of education and theatre to nurture individual rehabilitation and social transformation.

In 1788 the First Fleet of 11 British ships landed in Australia and founded a penal colony, settled by over a thousand people, prisoners and free. Many of the prisoners served seven- or 14-year terms and then became citizens of New South Wales. Distilling and transforming both historical studies such as Robert Hughes’s The Fatal Shore and historical fiction such as Thomas Keneally’s The Playmaker, Our Country’s Good takes up the story of how a group of these prisoners rehearsed and performed a production of George Farquhar’s city comedy The Recruiting Officer to commemorate the birthday of King George III. Two hundred years after the First Fleet’s arrival, Wertenbaker created a piece of epic theatre that probes the divide between authority and transgression.

Language and rehearsal

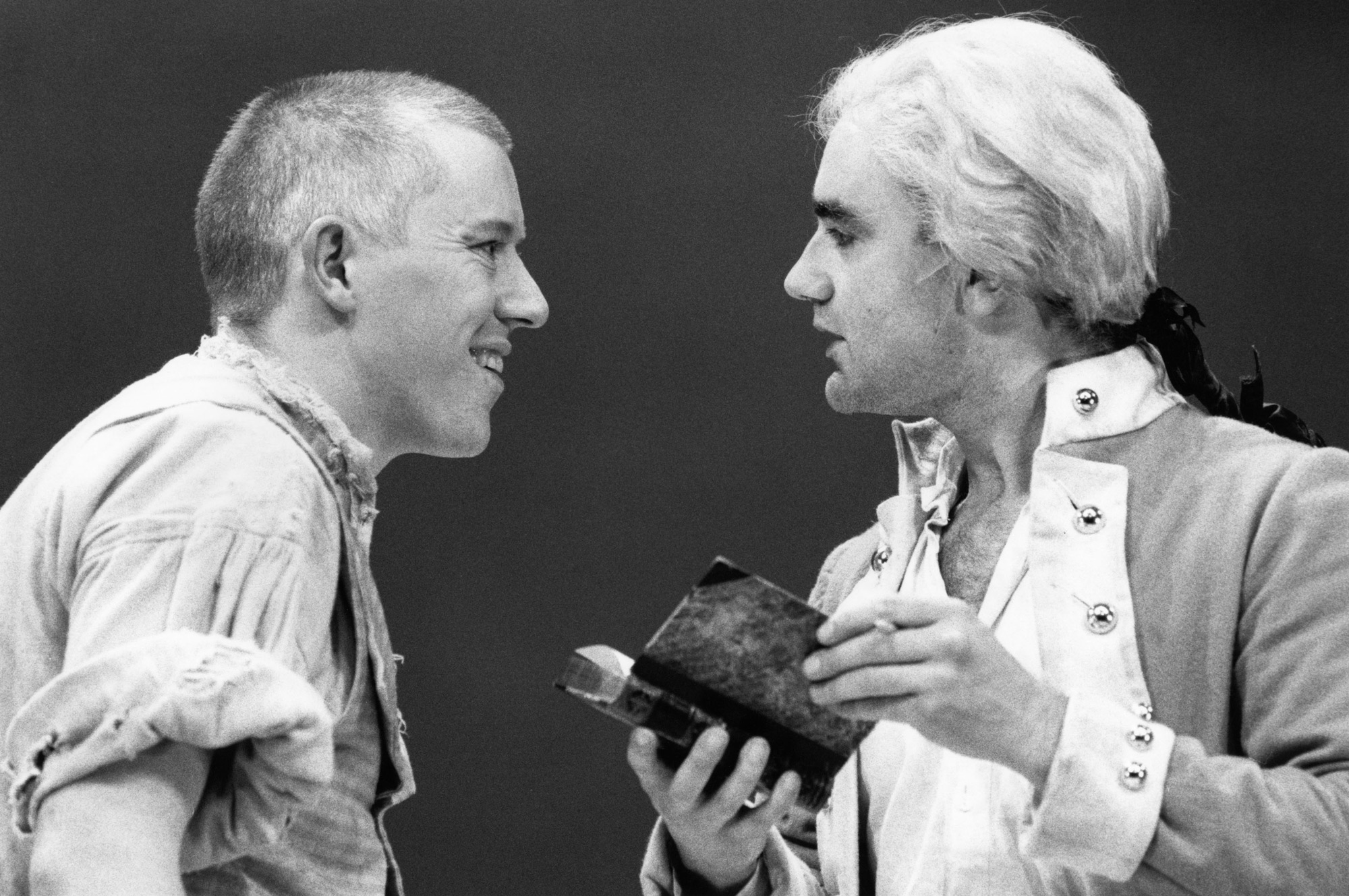

Wertenbaker’s play centres on Second Lieutenant Ralph Clark, who directed the play, and his convict cast: the defiant Liz Morden, the bookish John Wisehammer, the subdued Mary Brenham, the theatrical Robert Sideway, the cunning Dabby Bryant, the hardened Duckling Smith and the rebellious John Arscott. Some of the most extraordinary passages of the play depict characters finding language to transform their lives. Each act of the play opens with one of the convicts struggling to express the violence of his or her existence with inadequate language. The show begins with a vulgar and poetic monologue from Wisehammer about the voyage out: ‘Alone, frightened, nameless in this stinking hole of hell, take me, take inside you, whoever you are’ (Act 1, Scene 1). Words can barely describe the pain of forced transport. Wisehammer’s speech is punctuated by the spectacle of Sideway being whipped on deck, creating a juxtaposition that demonstrates the physical subjugation that accompanies the convicts’ psychological loss.

The second act launches with Liz Morden telling her life story: ‘Luck? Don’t know the word. Shifts its bob when I comes near. Born under a ha’penny planet I was’ (Act 2, Scene 1). She speaks in 18th-century slang, brilliantly reworked by Wertenbaker from original sources such as the New Canting Dictionary. Morden’s skillful manipulation of these canting codes marks her pride of membership in a criminal subculture, but cannot mask the brutality of abuse she experienced as a daughter, sister and citizen.

In contrast with these act-opening passages, other sequences show the convicts finding language that serves them, sometimes directly taking examples from The Recruiting Officer and other times translating into their own idiom. Arscott says his speaking his lines allows him the mental freedom to be someone else. Duckling rebels against playing a maid. Ralph Clark and Mary Brenham play out a scene from Recruiting Officer to speak to each other of love and desire and commit to a symbolic marriage:

And something tells me, that if you do discharge me ‘twill be the greatest punishment you can inflict; for were we this moment to go upon the greatest dangers in your profession, they would be less terrible to me than to stay behind you. And now your hand – this lists me – and now you are my Captain. (Act 2, Scene 9)

Most importantly, the cast recites their lines and refuse to stop their practice in order to protect Dabby, Sideway and Mary when an angry officer interrupts rehearsal to humiliate and abuse them. Brought to trial as an accomplice to some convicts who staged an escape, Liz Morden finally speaks to defend herself because of how she learned to carry herself playing one of Farquhar’s main characters – and because she wants to perform the play. Rehearsing the play allows the convicts to question the conditions that led to their punishment and to re-envision themselves as fully dignified human beings.

Authority and performance

In a Brechtian fashion, Our Country’s Good employs 22 self-contained scenes (divided into two acts) that jump forward in time. Each one bears a title that encapsulates what happens in the episode: ‘Punishment’ (Act 1, Scene 3); ‘A lone Aboriginal Australian describes the arrival of the first convict fleet in Botany Bay on 20 January 1788’ (Act 1, Scene 2). This technique encourages readers and spectators to focus on how the events unfold, not just on suspenseful revelations. This distancing structure particularly makes visible how the authority of the military officers affects the players. In Act 1, Captain Phillip, acting governor of the colony, philosophically approaches the contradictory yet connected task of superintending a jail while planning for an eventual civic society. His regiment includes Scottish Major Robbie Ross, who relishes corporal punishment and psychological terror; legal mind Captain Davey Collins; haunted midshipman Harry Brewer; and Lieutenant Will Dawes, who trains a telescope on the stars in the sky and aims to explore the plants and animals in the ‘new’ landscape. Their debate in Act 1, Scene 6 (‘The authorities discuss the merits of the theatre’) draws on Rousseau and the Bible as they argue about human nature and civilisation, order and transcendence; later Captain Phillip encourages Ralph to continue with the play with examples from Socrates and Plato. In this scene, then, Wertenbaker introduces and reveals the system of beliefs, values and ideas behind the actions of the colonial authorities. Do they wish to replace the theatre of hanging with the theatre of heightened language and noble sentiments, or do they wish to block the play entirely? What kind of society do they want to shape?

Significantly, this exposure of 18th-century ideology connects to the play’s thoughtful if understated critique and condemnation of British colonialism, most directly embodied by the presence of an indigenous Australian character named simply The Aborigine. The Aborigine witnesses the arrival of the English ship, and tries to understand the strange doings of its inhabitants. He watches the colonists reshape his land and contracts smallpox. His assessment of the colonial arrival is that it is a dream that has lost its way, a dream no one wants. ‘How can we befriend this crowded, hungry, disturbed dream?’ he wonders (Act 2, Scene 4). Wertenbaker’s inclusion of The Aborigine’s voice in the play provides a framing perspective and a different attitude towards narrating and interacting with the history represented. With these techniques, Our Country’s Good asks the audience to consider this history through the multiple perspectives of the convicts, the colonists and the colonised.

Punishment, power and playmaking

Wertenbaker fuses many rich intertextual sources in Our Country’s Good, none more important than the play within her play. The Recruiting Officer dates from 1706. It is a witty, provocative piece that joyfully exploits sexual innuendo and romantic plotting, but is driven by powerful class commentary regarding military service, the judicial system and marriage expectations. The two couples at the centre of The Recruiting Officer – Plume and Sylvia, Worthy and Melinda – join with comic types such as the buffoons Kite and Bullock and the country wench Rose, and social figures such as Justice Balance, the lady’s maid Lucy and army-lifer Brazen. Together, they disguise themselves, spy and undertake exploits to improve their financial situations, escape restrictive expectations and find love.

Cuttingly, Farquhar’s play depicts the injustices of how men without means are ‘pressed’ into military service by trickery and judicial complicity, as well as how women are trapped into a marriage market that controls their freedom. Like many comedies, the play paradoxically affirms the social order and provides a happy ending, while critiquing how hypocrisy distorts the society. The historical event of convicts performing this play in 1789 becomes in Our Country’s Good a demonstration of how we are cast in roles in life by circumstances beyond our control, but we also get to change ourselves, allowing the play to activate Farquhar’s themes and develop a parallel, connected exploration of punishment, power and play-making.

Doubling in paired productions

Our Country’s Good is a beautiful piece of literature, but its full impact depends on significant staging choices. Under Max Stafford-Clark’s direction, the premiere of Our Country’s Good at the Royal Court Theatre set an important precedent by employing an ensemble cast where actors doubled as both a prisoner and an officer. For instance, the actor who played The Aborigine also played the Madagascan prisoner Black Caesar and the officer Watkin Tench. The actor who played Mary Brenham doubled as the priest. The actor appearing as Captain Phillip became John Wisehammer. Actors signalled their change of character and status simply by taking off or putting on a uniform coat and hat. The cast also played across race and gender in assuming officer roles, all while switching between the wide range of regional dialects carried by the characters. Likewise, Our Country’s Good performed in repertory with a full revival of The Recruiting Officer, also directed by Stafford-Clark using the same cast. At every turn, the productions doubled and paired story, character and identity. In this way, both history and identity are portrayed as both determinative and fluid. The play multiplies the options for stories to be retold and revised. This staging choice carries not only important social commentary, but also theatrical thrill.

Our Country’s Good ends sounding a note about the thrill of learning and the potential within us to change, develop and refashion narratives. That thrill backs right up against how the play acknowledges loss, deprivation, prejudice and the flawed nature of society, creating a particular tone of mournful celebration. Titled ‘Backstage’, the final scene of the play culminates in Wisehammer speaking his newly written prologue for the convict’s performance of Farquhar. Endings become beginnings, society’s destitute transform into aristocracy and backstage flips to become the featured scene.

Wisehammer

From distant climes o’er wide-spread seas we come,

Though not with much éclat or beat of drum,

True patriots all; for be it understood,

We left our country for our country’s good;

No private views disgraced our generous zeal,

What urg’d our travels was our country’s weal,

And none will doubt but that our emigration

Has prov’d most useful to the British nation.Silence.